How Toxic is the Air in Your Home?

Unhealthy indoor air is surprisingly common and shockingly insidious, causing asthma, heart disease, cancer, and millions of deaths a year. This DIY fix-it guide is for anyone who breathes.

“We’ve spent decades clearing our air outdoors across the United States… and made little or no progress cleaning our air indoors.”

—Rob Jackson, Stanford professor

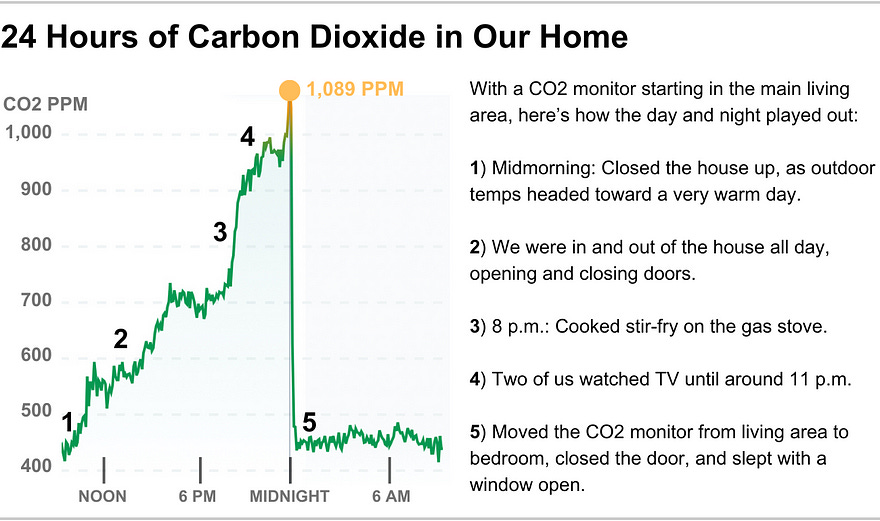

On a recent evening, carbon dioxide in our house spiked to levels that can reduce brain function, hamper sleep, induce stress, and raise the risk of respiratory illnesses and chronic diseases. This was not some unusual event. There were no alarms, no 9–1–1 call. It was just a regular day and evening in which my wife and I (and our dog) did some breathing and eating and other normal life stuff.

When we went to bed, we slept with a window open, and CO2 levels fell suddenly back to a safe zone and stayed there through the night.

I didn’t realize any of this had happened until the next day, when I looked at data downloaded from my favorite new tech toy: a carbon dioxide (CO2) monitor. The episode became an experiment, albeit a decidedly non-scientific one, because my wife had noticed the spike that night and, curious about it, brought the monitor into the bedroom.

Here’s the CO2 fluctuation we experienced, from 9 a.m. one day until 9 a.m. the next:

Carbon dioxide is a common pollutant from combustion, and a chemical we emit each time we breathe out. According to numerous studies reviewed as part of an analysis in the journal Indoor Air, CO2 concentrations as low as 1,000 ppm — a level found in many homes, offices and other buildings — can induce drowsiness, headaches, reduced cognitive ability, and heart-rate variations.

In our little “experiment,” concentrations reached the risky threshold in the 1,000-square-foot main living area of our house, which has 10-foot ceilings. If you live in a tiny house, or a teensy New York City apartment, fuhgeddaboudit — the smaller the space, the higher the concentration of CO2, given the same amount of breathing and other polluting activities.

Here’s the kicker: CO2 can serve as a loose proxy for numerous other unhealthy chemicals and particles that build up in enclosed spaces. Think of high CO2 levels as an indicator that if other other airborne pollutants or pathogens are being generated in the home, they have likely built up, too, creating additional hidden risks for brain health, heart and lung problems, cancers, many other chronic diseases, and even viral illnesses.

A new research paper from a team led by Rob Jackson, PhD, a Stanford professor of energy and environment, reveals an outsized indoor pollution risk from gas stoves and ovens, in particular, estimating they are responsible for as many as 200,000 existing cases of pediatric asthma in the US, and tens of thousands of adult deaths. (The specific findings are discussed below.)

But there are many other sources of indoor pollution that can make air in many homes more polluted than the air outside at times, research shows. That puts the health of everyone in a home at risk. Especially vulnerable are children, older people, individuals with allergies or asthma, and anyone with heart or respiratory conditions.

“We’ve spent decades clearing our air outdoors across the United States… and made little or no progress cleaning our air indoors,” Jackson said by email.

Because most indoor air pollution is invisible, and much of it packs no smell, we have no clue about the serious degradation of health we experience daily in our homes. Polluted indoor air can have greater health consequences—for adults and children—than bad outdoor air, because most of us are indoors more than 90% of the time.

Think about it: You likely spend around a third of your 24 hours sleeping (or trying to sleep), and probably several more plopped in front of screens or doing other home stuff. If you work indoors, there’s another third of your day. Based on life expectancies, it’s been estimated an average American spends 54 years inside their home.

Given the alarming CO2 levels I discovered in my own home, and having since dug deeply into the science of indoor air pollution, my skepticism about the risks has given way to genuine concern for anyone who lives and breathes indoors.

If that’s you, read on.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Wise & Well to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.